July 23rd is Smokebeer preservation day: On this date in 1635 the first smoke free malt drying machine was patented. As a consequence smoke free beer became dominant all over the world and the original smokebeer was turned into a rare, almost extinct speciality. Only in Bamberg the traditional fire kiln was continuously preserved: At Schlenkerla the fire still burns today in the maltings.

Overview of program for smokebeer preservation day at the Schlenkerla brewery pub

A great many stories have grown up around the origins of Smoked Beer. Some are quite imaginative, others are a bit strange. In an oft told legend, when a brewery in Bamberg burned in the Middle Ages, the malt was smoked accidentally. As unexpectedly, Bamberg's citizens enjoyed the flavor of the resulting brew, thereafter, the technique was applied on purpose. While a funny anecdote, it's far from the truth.

Before addressing the question, who invented smoked beer, one needs to ask how long beer has been in existence at all.

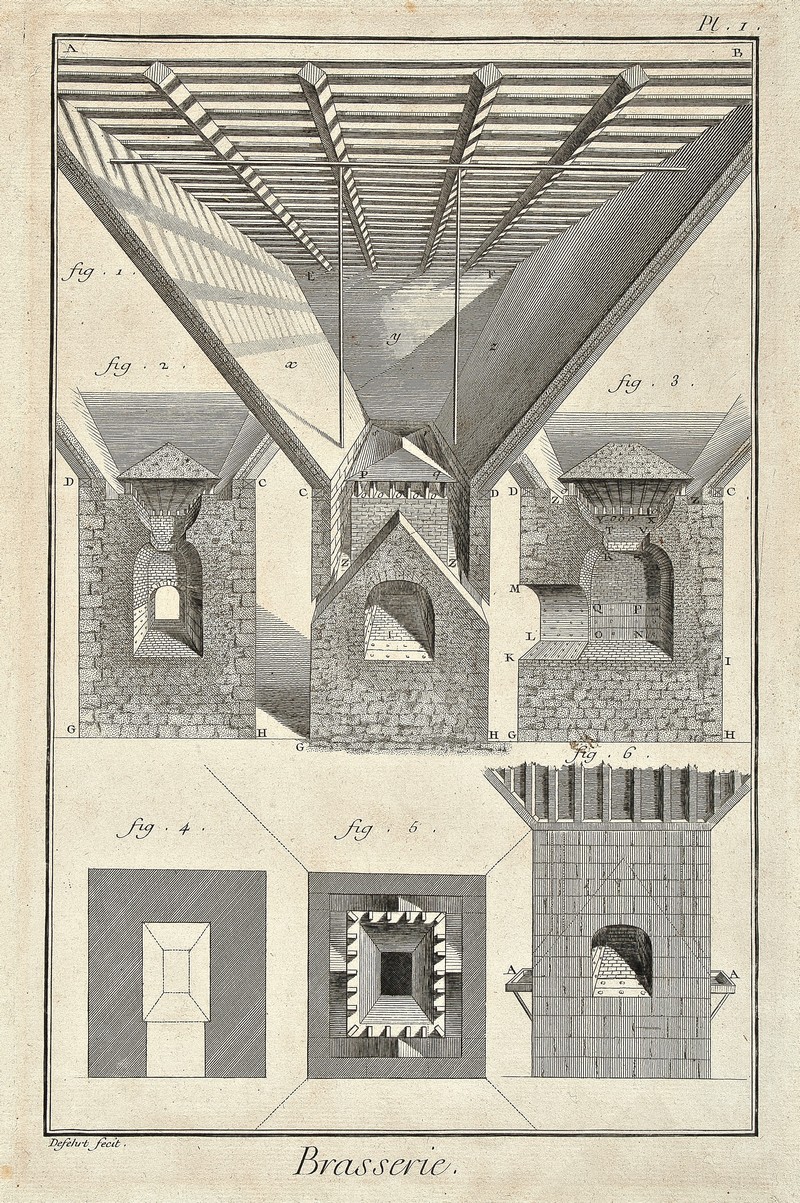

Technical schematics of a smoke kiln from about 200 years ago.

Kilns where back then part of the brewery, hence the term "Brasserie" (the drawing is french). Mere malt producers were founded only after the 17th century in the process of industrialization of brewing. Today almost all breweries receive their malts from industrial malting companies.

In 2018, in an excavation site near Haifa, Israel, scientists discovered what is believed to be the oldest brewery known to man, dating back 13,000 years. Already known was a cultural site in Göbekli Tepe, Turkey, where humans brewed beer some 12,000 years ago. Both sites are in the Fertile Crescent, a half-moon shaped area in the Middle East known as the home to the archetypes of many grains. (Today, this area comprises Israel, Syria, Jordan, Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and according to newer interpretations, Egypt as well.) The assumption is that humans first discovered there how to use grain for nutrition (i.e., beer and bread) and consequently how to cultivate this grain purposefully, thus the invention of agriculture and the basis of our modern world. Beer hence played an important role in the first high cultures, e.g., with the Sumerians and Egyptians some 5,000 years ago. Brewing descriptions are found both in hieroglyphics and cuneiform writings. It's likely that cuneiform was invented by clerks just for the purpose of documenting beer and grain for taxation. Literature came later. Babylonians are known to have had more than 20 beer varieties. And both Romans and Greeks consumed plenty of beer in addition to the then more modern wine.

The basic principle of beer brewing has not changed in the past 13,000 years. The starch of the grain is broken down into sugars, which are then fermented by yeast to alcohol. However, there have been, and still are, differences in the technology applied for this process. Egyptians had a so-called cold beer method, in which a special beer-bread was mixed with cold water (and sometimes also fruits) and then fermented. Sumerians used a technique closer to modern brewing, a warm beer method, in which the mash (the water-grain mix) was boiled. Humans had very early discovered that germinated and dried grain yields a better fermentation and hence a better beer; today this process is called malting.

There are two different methods for drying germinated grain: air drying and fire drying (air malt and kiln malt). With fire drying, it was unavoidable that the smoke from the fire penetrated the malt and gave it a smoky aroma. Presumably, fire kilns have been around since the Bronze Age some 5,000 years ago. Clues to that are e.g. to be found in Bab edh-Dhra (today Jordan) near the Dead Sea. In moist climates, e.g. in Central Europe, the fire kiln often was the only feasible way to dry the grain sufficiently. Such a fire kiln and some smoked barely grains were found in the grave of a Celtic chieftain from around 550 B.C. in Hochdorf, Germany. Furthermore, in such climates it was essential for survival in winter that grain did not get moist. Therefore, the storage compartments in houses were connected to fireplaces in order to keep away moisture and also mold. As a side effect, the smoke probably ensured that rodents did not spoil the grain. Last but not least, cooking was also done with an open fire, and so smoky flavor was present in all foods and of course also in beer.

In short: smoked malt and smoked beer have been around at least for 5,000 years, and in Central Europe presumably all beers had smoky flavor. When drinking an Aecht Schlenkerla Rauchbier, one has in effect a piece of beer history with every swallow!

drying of malt at Schlenkerla with open fire (and thus smoke)

For thousands of years, brewing technology had not changed considerably. But then in the course of the industrial revolution in England, brewing (as all crafts) underwent enormous changes. One date stands out: on 23rd July 1635, Sir Nicholas Halse of Cornwall received a patent by King Charles I for his new type of kiln:

"for the dryinge of mault and hops with seacole, turffe, or any other fewell, without touching of smoake, and very usefull for baking, boyling, roasting, starchinge, and dryinge of lynnen, all at one and the same tyme and with one fyre"

Suddenly it was possible to produce smoke free malt in any climate and with any fuel! The latter fact made this new production method much more cost effective than the traditional smoke kilns; for the smoke kilns, high grade wood and good smoke aroma were (and still are) important. Subsequently, more patents on further improved kilns were issued. And since the new technique was cheaper and less of a fire hazard, it soon replaced the old smoke kilns in England. Since England led the rest of the world with industrialization, it took more than 150 years for the invention to make its way to Germany. Around 1800, Georg Sedlmayr the Elder from the Spaten brewery (Munich, Bavaria) was one of the first brewers who switched from the old "Bavarian kiln" (a smoke kiln) to the modern "English kiln" (a kiln without smoke). By the way, his son Georg Sedlmayr the Younger was the one who made the spectacular espionage trip to England in the 1830s to bring back important beer technology improvements to Munich, thus laying the basis for today's worldwide reputation of Bavarian beer (and also indirectly for Pilsener style and all lager beers).

As in England, also in Germany, the new cheaper technology soon replaced the old expensive one; and by 1900 almost all smoke kilns had vanished. All? No, in Bamberg at the beginning of the 20th century, there still were four breweries that made smoked malt: Brewery Polarbär (closed in WWII); brewery Greifenklau (closed its malting operation in the 1970s); brewery Spezial, and of course Schlenkerla. And the latter two have - as the only breweries in the world - preserved the old tradition of fire kilns continuously until today.

Due to the craft beer revolution over the past years, old beer styles have become popular again. Since the big commercial malting companies have begun industrial production of specialty malts, today one can find a number of new smoky beers made with industrially produced smoke-flavored malts. The old production technique with a brewery-owned open fire kiln has however been preserved until today only by Spezial and Schlenkerla in Bamberg; thus this unique beer style is often referred to as "Bamberg Smoked Beer" or, in German, "Bamberger Rauchbier".

Since the new cheaper methods of producing smoke-flavored malts at industrial scale are endangering the traditional more expensive smoke malting technique, the breweries Spezial and Schlenkerla are now passengers in the Ark of Taste from Slow Food®. As the old proverb says:

Preserving tradition means to keep the fire burning, not to conserve the ashes.

In the Schlenkerla maltings, this fire burns quite literally still today.

read more: The brewing process of Smokebeer | Smokebeer varieties | Find Smokebeer near you